Double, double, toil and trouble, fire burn, and Wheel of Time Reread Redux bubble!

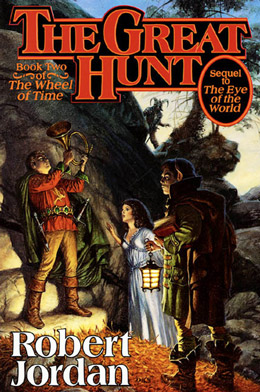

Today’s Redux post will cover Chapter 31 of The Great Hunt, originally reread in this post.

All original posts are listed in The Wheel of Time Reread Index here, and all Redux posts will also be archived there as well. (The Wheel of Time Master Index, as always, is here, which has links to news, reviews, interviews, and all manner of information about the Wheel of Time in general on Tor.com.)

The Wheel of Time Reread is also available as an e-book series! Yay!

All Reread Redux posts will contain spoilers for the entire Wheel of Time series, so if you haven’t read, read at your own risk.

And now, the post!

Chapter 31: On the Scent

The Cairhienin Reader rose. “Aes Sedai?” she said softly. Verin inclined her head, and the Reader made a full curtsy.

As quiet as they had been, the words “Aes Sedai” ran through the crowd in tones ranging from awe to fear to outrage. Everyone was watching now—not even Cuale gave any attention to his own burning inn—and Rand thought a little caution might not be amiss after all.

I’ve had various criticisms over the course of the series both over how the Aes Sedai are portrayed and how they are perceived, but overall I do think Jordan did a very nice job of blending his own world’s gender-flipped respect of women in power, with our own world’s inherent fear of the idea of a woman with power, particularly one with mystical power—a fact which continues to be reflected in countless stories and depictions (and various historical atrocities, natch) into the present day.

The Whitecloaks call the Aes Sedai “witches,” and that is a loaded word. I was initially uncertain whether Jordan realized to what extent that term is loaded, but he certainly had at least some idea, as indicated by the fact that he put it in the mouths of the most blatantly intolerant group of bigots on his entire fictional continent. He most likely knew very well to what extent that term has been used to condemn, intimidate, and control women who have dared to assume positions of influence and power in their communities through knowledge of herbcraft, midwifery and medical lore, especially that associated with female concerns in particular, which historically in Western culture have long been tainted with the stigma of uncleanliness and sin, and thus made it easy to extend that condemnation to those who dealt with those “unclean” issues.

Calling Aes Sedai “witches,” therefore, carries far more powerfully negative connotations than just accusing them of being people who wield magical power. It carries with it an accusation that is very specifically leveled against women. It is an implicit accusation that women holding any sort of power at all is dangerous, unnatural and wrong, and it is (therefore) a phenomenon which must be stamped out wherever it occurs.

Whether the Whitecloaks themselves took that implicit accusation to that extent is irrelevant (though I would argue that their general treatment of women, and Valda’s later treatment of Morgase in particular, bolsters the notion that they do in fact take it to that extent), because it is the real-world parallel that I think is being commented upon here.

That’s how I took it, at any rate. And I continue to be pleased that Jordan’s response to that implicit accusation is basically what most sane people’s response is: that power itself is neutral, and it is how it is wielded that makes the difference, and that that difference doesn’t actually have anything to do with gender at all, but with the character of the person involved.

Perrin slouched at the table, studying his hands clasped on the tabletop. To his nose, the room smelled of beeswax used to polish the paneling. It was him, he thought. Rand is the Shadowkiller. Light, what’s happening to all of us?

I distinctly remember this revelation as being one of the coolest in the entirety of TGH, probably only rivaled by the conversation with Artur Hawkwing at the end of the book for “self-realization” moments. Even if, admittedly, it’s not actually Rand having the realization moment himself here. Basically, there are few things that are going to goose my geek meter more awesomely than finding out that sentient wolves have such respect for you that they’ve given you a name, all right, even if you can’t talk to them. Perrin being “Young Bull” is cool, don’t get me wrong, but Rand being “ Shadowkiller” is boss. I’m not even going to bother being sorry about it.

“There are Darkfriends among the high as well as the low,” Verin said smoothly. “The mighty give their souls to the Shadow as often as the weak.” Ingtar scowled as if he did not want to think of that.

Yeah, I bet he doesn’t.

“They will know I’m no lord. I am a shepherd, and a farmer.” Ingtar looked skeptical. “I am, Ingtar. I told you I am.” Ingtar shrugged; he still did not look convinced. Hurin stared at Rand with flat disbelief.

Burn me, Perrin thought, if I didn’t know him, I wouldn’t believe it either. Mat was watching Rand with his head tilted, frowning as if looking at something he had never seen before. He sees it, too, now. “You can do it, Rand,” Perrin said. “You can.”

“It will help,” Verin said, “if you don’t tell everyone what you are not. People see what they expect to see. Beyond that, look them in the eye and speak firmly. The way you have been talking to me,” she added dryly, and Rand’s cheeks colored, but he did not drop his eyes.

I remember that basically what I got from this is that if I were to be dropped into Randland all unexpected, that people would assume I was nobility too, just because I would assume I had the right to look people in the eye and assert my own opinions. This pleased me—as no doubt it was meant to. Heh.

But I think there is something to be said for that image—that many modern folk, if mysteriously transported into less modern times, would mostly likely be taken for (crass) nobles simply because many people these days have unconsciously internalized the idea that a person has inherent worth independent of their financial status, and fuck you if you think otherwise. This is not to suggest that class warfare is a thing of the past, because it most certainly is not, but these days it is most certainly being carried out on a much more subtle level than the historically popular practice of overtly assuming that if you were a poor commoner, you must have some innate flaw that meant you deserved it. That assumption is still there, but it is carefully camouflaged; it is no longer acceptable to espouse that idea openly. Which isn’t awesome, obviously, but driving it underground is a step toward its eventual elimination, or so I hope.

But my point is, there’s nothing like reading about class differences in pseudo-historical settings to make you realize how much times have changed in the real world—thankfully, for the most part.

Aside from everything else, it is nice, post-TGS, to know that Verin’s motives in all of this are more or less completely pure. Which is weird, maybe, when we know that she actually is Black Ajah, but knowing that she is also a (completely awesome) double agent pretty much clears any suspicion that she has anything other than Rand’s survival and wellbeing in mind in everything she does. It’s quite a source of stress relief, really, when reading the early books now, when previously we had no such assurance. Ahhh.

…Aaaand I was going to continue on, but the next two chapters really need to go together (and also deserve to have proper justice done to them), so we’re gonna stop here. Have a lurvely early fall weekend, y’all, and I’ll see you next Tuesday!

I don’t think the days of explicit class warfare and blaming poverty on the poor are anywhere near over unfortunately.

I’m a millenial, so I know that I’m a noble. I’m just waiting for everyone else to realize that I’m a special snowflake.

When people are openly blaming poverty on capitalism you know we have a long way to go.

@3.

Capitalism as a social system is specifically structured for impoverishment. That is, what it does logically (the profit imperative driving surplus extraction means that subsistence level is guaranteed for the mass number of workers under capitalism) and historically (It is after all, the separation of the means of production from the producers and thus the rise of market compulsion that is the historical starting point of the working class).

Hmm…I think you are right in that he is probably more playing on our own preconceived notions of women and power, but now I wonder if the use of ‘witch’ as a pejorative makes sense in a society where a)men are basically the ones responsible for the fall (an onus often wrongly associated with women in our culture) and b)women have had political and magical power throughout their history.

If I recall the logic of the Whitecloaks is that they distrust the Power entirely, so perhaps in that sense it makes sense and ‘witches’ is meant (in their world) as a term to evoke a sense of a person grasping for power they shouldn’t be, regardless of gender. But since men typically aren’t going to live long enough/be sane enough to be prominent with that power, you just aren’t going to encounter any. Is there a similar term for men? Some kind of gut prejudice regarding women having power that men can’t have? I wonder if there was a similar group in the Age of Legends that reviled Aes Sedai in general.

@@@@@ 4

Capitalism is also the mode of production that has created the most prosperity ever in world history, according to Marx himself. Incentives and initiative to create your own business have a power to create wealth that is unsurpassed, when compared to what came earlier (feudalism and mercantilism). What Marx couldn’t have foreseen (considering he lived in the 19th century) was that the way labor and capital divided the products they made didn’t necessarily have to be the same way that was happening in 19th century Europe. Political action among the laborers did create conditions for a more equal sharing, with rights being granted (and enforced by the state) and with the salary of the laborers not necessarily diminishing to the minimum necessary for subsistence. The burgueouis state, after many struggles, allowed the laborers to organize themselves in trade unions and to demand stuff from the capital owners. Marx had foreseen that this would never happen and armed struggle and overhaul of the entire system was the only way for the laborers to get better treatment in the end. As I said, he had an excuse to think so, considering what he experienced and when he died. You don’t, considering you live in the 21st century and you’ve seem what happened afterwards.

Going back to what Leigh said, I don’t think I’d be considered a noble if I travelled back in time or went to another world. Part of my ancestry is Japanese, and if I went back to feudal Japan they wouldn’t consider me a noble just for being brash. They would consider me a barbarian that didn’t know any better, and that would insult everyone all the time with brazen ways. There are ways that someone is expected to behave in a society, and if you don’t conform to that, you’ll be identified as a foreigner quite easily.

A commenter in the original reread noticed something that I noticed in this re-reread and was wondering about: the wind that arose when Rand burned Selene/Lanfear’s letters. She is obviously tracking Rand in some fashion (witness her rather sudden appearance at the Illuminators’ chapter house) but is she somehow actually watching Rand all or most of the time? And if so, how? Anybody got any ideas?

@@@@@ 5

Good point. Also, worth noting that “witch,” while it has female connotations in the present day, is technically gender neutral and was viewed as such for most of history. Many of the accused in Salem were men, and there is certainly evidence in the Medieval Era in Europe that men could be accused of witchcraft.

And while I think the Whitecloaks are obviously misogynistic pigs, in this case their hatred doesn’t seem to be focused on women per se, but rather users of the One Power. And since the odds are they almost never come across a true male channeler, whereas seeing/interacting with female channelers is a relatively commonplace experience, its perfectly plausible to come to the conclusion that they’re using “witch” in the classical sense of “someone who is meddling with forbidden or dark powers” and not in the more modern “unpleasant and also possibly magical female” sense. It makes more sense in the context of the world anyway.

I agree with #7; there was one point where Rand thought he smelled her perfume. I figured that she’s probably making herself invisible (I think she can) and Rand is in fact smelling her. Why would she let him out of her sight if she could avoid it?

Whitecloaks despise everyone. Even other Whitecloaks.

Lisamarie @5

Yes, exactly.

BillinHI @7

I think you’re on to something, but no ideas on how Selene could be monitoring Rand.

“Don’t worry, you would need both Choedan Kal to break the world.” Even if you don’t destroy the world, you can do a lot of damage, Verin.

How does Verin know that the statue is the male Choedan Kal if they didn’t even stop in the village? Did the Brown or Black Ajah know where it was before the excavation?

@12 birgit

A statue that large probably distorted the ground around it. Otherwise there would have been no reason to start excavating a giant hole right outside the city would there?

If some part of the statue was sticking out of the ground like the hand of the female statue on the Sea Folk islands, then they would know what it was through simple process of elimination. The Aes Sedi had vague records of the Choden Kal having been made and what they looked like.

I hope the new WoT Encyclopedia lists all of the wolves names for the Forssaken.

Thanks for reading my musings.

AndrewHB

I would put it a tad more cynically than you did. Most Westerners would be viewed as noble by the peasantry of Randland, because most Westerners view their own needs as taking priority over everything else, without even realizing it, especially when in an uncomfortable situation. What is often communicated is “I’m more important than you.” Whether we intended to or not.

Come on people! If you saw someone wearing a ten thousand dollar suit running around with George Clooney, an international diplomat, and an army captain, would you REALLY believe them if they said the worked at a supermarket. Ummmm…. no, you definitely would not. He is not being accepted just because he knows how to strut. That’s absurd.

@6 Capitalism straight up requires poor people. It’s part of the system. Honestly, whether it creates more wealth than other systems seems irrelevant when most of that wealth is concentrated within a minority.

Finally, last I checked we were against stereotyping large groups of people here, including millenials.

@16 givemeraptors

re: nobility

I agree, it’s the clothes, not the demeanor.

We could 21st-century-self-esteem all over Randland and would be considered nothing but insolent peasants. But give us prêt-à-Moiraine clothes and we’d be noble as fuck.

re: stereotyping

Oy, don’t stereotype us as the non-stereotyping kind!

@16:

There are certainly very poor people in the United States. And yet, somehow, they rarely starve to death. The vast majority of people classified as poor in this country have relatively stable living environments, access to running water, access to medical care, enough money to consume unnecessary items such as soda, cigarettes, more than one pair of clothes… the list goes on.

What we consider poor in our society today is a far, far cry from the 19th and early 20th century. That is a direct result of capitalism. Now, capitalism without some common-sense restraints, run amok? Just as bad as any other system. But without the profit incentive, no other system has shown the ability to regularly innovate and create. Its the innovation and the rewarding of creativity that has helped us achieve the technology and surplus wealth that allows people who quite literally provide no value to the system whatsoever to live better than a large percentage of the rest of the world lives right now, to say nothing of previous centuries.

When we say poor, we mean in relation to the statistical mean… but that’s a completely idiotic way to judge if a system is working or not.

anthonypero @@@@@ 18

Hear, hear! Plus it’s the tax receipts this system generates that pay for the welfare states and the proper healthcare systems we have (at least in Europe ;) ).

The are a lot of things that are wrong or imperfect with the capitalist states but I wish I could take a few folks home back in time to see how we lived behind the Iron Curtain! They pretended to pay us and we pretended to work…

As for Rand’s nobility, I think there is a combination of factors: 1- Moiraine’s make-over; 2- his demeanor; 3- the Cairhienin already thought him a noble so 1 and 2 clinched it. I agree that just being confident wouldn’t have been enough to pass for an aristocrat.

@18 and 19

The only reason one can say that things are relatively better in the U.S. than they’ve ever been is because a large part of America’s wealth is built on the backs of people in other parts of the world. The abject poverty and dictatorships are still there, they’ve simply been displaced to other countries.

In WoT terms, it would be like the governments of Randland supporting the Seanchan because they get cheap power-crafted items out of it.

Have other economic systems done better? Not really, frankly they’re pretty much all on the same level.

BillinHI @7

Well, even Moiraine had a rudimentary means of tracking the three boys using the coins. It’s not implausible, given the huge disparity in skill between Lanfear and Moiraine that Lanfear would have a means of doing so through the letters or some other means.

LisaMarie @5

Pretty much. IIRC the Whitecloaks think the One Power is not meant for mortal hands and should be used by the Creator only. Hence the use of the epithet witch. It’s partly the belief that they are evil for using powers not meant for them and also partly frustration at the fact that the White Tower is so entrenched – politically, physically, even militarily- they have no means of dislodging them. They don’t even have any means of challenging individual witches. The only individual Aes Sedai they’ve “put on trial” were already dead during the proceedings. They believe they are right and don’t have the might to assert it and the impotence is galling to them.

Do we ever hear if there was a similar group in the Age of Legends? Their first assertion is kind of illogical; unless they are saying Shaitan is somehow responsible for people being able to channel.

Their other frustration possibly has merit though, from a certain point of view ;)

“These hands were meant for a smith’s hammer, not an axe.” Oh, to think ahead to ToM, and know how beautifully true these words are, in ways we couldn’t imagine at the time!

Speaking of comments with foreshadowing/greater meaning, Verin saying she would love to meet Selene is darkly ironic, since wasn’t it confirmed that she met Lanfear in the Tower at some point? (Probably during book three, since that’s when Lanfear was running around as Else.)

Re the Choedan Kal: I don’t think I mentioned it before, but I always wondered why Galldrian was having it dug up. Surely he didn’t know what it was, and was trying to keep it away from Logain/Taim/whatever other false Dragons showed up? I imagine he might make that excuse if someone asked him, but probably it was more of his bread and circuses mentality: not just fireworks and festivals, but latching onto something ancient and grandiose from the Age of Legends to distract the people (and incidentally, make himself look even more powerful and mighty, not to mention how it suggested he dared to stand against the White Tower by associating with something of saidin; Daes Dae’mar strikes again!).

Also, it was noted on the WOT Encyclopedia how odd it is for Verin to know (or claim to know) Logain’s strength, but considering what we learn later of just how strong in the Power he is, I think Verin’s claim here isn’t just odd, but wrong. Which suggests to me she only made it because a) no one in the room could possibly know it to be untrue and b) she thought it would discourage Rand from any dangerous experimentation with it.

As if we need any more testimony to his awesomeness *sniff* but I always liked how Hurin stood up to Ingtar here. Mostly because of the loyalty it showed, but also because even without knowing yet that Ingtar was a Darkfriend, I had fast become done with him and his “I must have the Horn!” schtick. So to see someone else step in and cut off the one-note annoyance, even if he did end up having to back down, was great. (Oh and yes, Ingtar’s reaction to Verin’s comment about Darkfriends among the high is so clear in hindsight. It also suggests to me that even if she never revealed her Darkfriend nature to him, she was very well aware of his allegiance.)

Not much to say about the Aes Sedai/”witches” issue except to agree I don’t see how Jordan could not have known the history and connotation of the word. Even if he didn’t know just how deep it ran and how horrible, he knew enough to put it in the mouths of Whitecloaks (and, if we’re right about the attack on Demira Sedai, Taim and his men, which is significant considering how much the Black Tower was about giving power and respect back to men again after the taint and the Breaking). And that says it all as far as I’m concerned.

Of course Leigh loves the moment with Perrin and his realization: it’s another of her “someone realizes one of the heroes is awesome and badass” moments. What’s interesting is while later on these moments tend to come from outside perspectives, minor characters, or at least secondary or tertiary characters, here early on it’s one of the Superboys himself realizing it about another. It’s rather important and necessary (and fun) for the heroes to realize this about each other before we get to see others in the world doing the same. Makes it hit home in a whole different way.

And speaking of how others think of you, I never really thought about it the way Leigh puts it, but she’s quite right how critical and wonderful it is that people in modern times (for the most part) no longer judge based on class but believe in intrinsic worth. We still have a long way to go, since even aside from the subtle classism she mentions, we all know quite well there are other criteria people still use to insist (however much they deny otherwise) some people have less value than others. But it’s still a big step in the right direction, and to see this view considered one of simple common sense from the WOT heroes, especially the Superboys, is quite heartening.

The fact the other people in the world assume they must be nobles because of their “arrogance” is ironic, since the very view the boys hold is one we’ve seen isn’t held by a lot of actual nobles. It rather seems like a commentary on the divide between what the world actually is and what we wish it was–namely, that those who lead actually deserve to, that they are a better group not because they believe they are, but because they believe there are no ‘lessers’ and do all they can to help and look out for them, to treat them fairly. The events leading up to Tarmon Gai’don, among many other things, involve removing the cruel, selfish, arrogant leaders from power and replacing them with people who actually deserve the roles precisely because they don’t want them, because they will actually act decently, courageously, and well, nobly. As Leigh pointed out on a previous entry. The fact this result makes the world more like it was in the Age of Legends, and also a world far more balanced, is also not an accident. Idealism is not dead!

@5 Lisamarie: If there was such a group during the Age of Legends, they surely must have kept quiet and subtle about their views. Even if the Age of Legends wasn’t as perfect as we were originally led to believe, it couldn’t have been a utopia of the sort described to us if there was that kind of open, and nasty, dissent.

@7 BillinHI: Whether or how she might have been watching Rand all the time, I don’t know, but we do learn later from Moridin that he has the ability to track ta’veren through the Pattern, and I believe it was said Lanfear had this ability too. Or else it was just implied from how she was always able to find Rand like that.

@8 Andrew: Good analysis. I think Leigh’s point is still valid though, that even if the Whitecloaks didn’t know the other implied meaning, or intend it, Jordan must have, or at least knew how the word would be read by most of his audience. So even if those connotations aren’t there in-universe, we could be affected by them, and many probably were.

@14 AndrewHB: That would be awesome, if unlikely. But I bet we’ll at least get translations for all their Old Tongue names.

@16 givemeraptors: LOL, love your analogy!

@21 alreadymad: And as much as I hate to say it (and generally think it’s wrong to generalize), I have to say the Whitecloaks have a point. Obviously wonderful and amazing things have been done with the Power, and it was a big reason why the Age of Legends was so wonderful…but rather like Gilded Age America, the beauty and wonder and prosperity were simply a mask hiding the inequities and flaws beneath, ones which made it easy to abuse the Power once people were given the means and leave to do so by the Dark One’s touch. And of course the Power was what created the Bore as well as the Breaking. Even if it was also necessary to undo this mistake and save the world, it can’t be denied that One Power users have done a lot to ruin and harm the world too. Of course if it wasn’t the Power it would have been something else people used to hurt others and gain prominence, and it’s narrow-minded and prejudiced to dismiss the Power entirely as not meant for mortals, rather than acknowledging its dangers and insisting that like anything else in life it needs to be carefully considered, regulated, and wielded with proper care and diligence. But it’s at least a bit understandable where Lothair Mantelar was coming from.

@22 Lisamarie: Again, not that I know of, and I really can’t see how such a group could exist in a utopia. Not unless they were far less aggressive and agitant about it. A passive group that merely stated their views and exercised a calm rejection would have been more likely allowed. Kind of like Jain believers or certain Buddhists…or, well, those who follow the Way of the Leaf. Only about the Power rather than violence.

Reminds me of the 1632/Ring of Fire books.